Nepenthes rajah

| Nepenthes rajah | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Large lower pitcher of Nepenthes rajah. Mount Kinabalu, Borneo. | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Core eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Nepenthaceae |

| Genus: | Nepenthes |

| Species: | N. rajah |

| Binomial name | |

| Nepenthes rajah Hook.f. (1859) |

|

|

|

| Borneo, showing natural range of Nepenths rajah highlighted in green. | |

| Synonyms | |

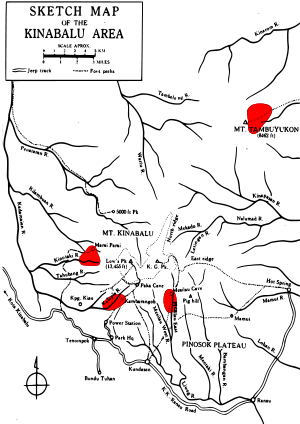

Nepenthes rajah (pronounced /nɨˈpɛnθiːz ˈrɑːdʒə/) is an insectivorous pitcher plant species of the Nepenthaceae family. It is endemic to Mount Kinabalu and neighbouring Mount Tambuyukon in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo.[2] N. rajah grows exclusively on serpentine substrates, particularly in areas of seeping ground water where the soil is loose and permanently moist. The species has an altitudinal range of 1500 to 2650 m a.s.l. and is thus considered a highland or sub-alpine plant. Due to its localised distribution, N. rajah is classified as an endangered species by the IUCN and listed on CITES Appendix I.

N. rajah was first collected by Hugh Low on Mount Kinabalu in 1858, and described the following year by Joseph Dalton Hooker, who named it after James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak. Hooker called it "one of the most striking vegetable productions hither-to discovered".[3] Since being introduced into cultivation in 1881, Nepenthes rajah has always been a much sought-after species. For a long time, the plant was seldom seen in private collections due to its rarity, price, and specialised growing requirements. However, recent advances in tissue culture technology have resulted in prices falling dramatically, and N. rajah is now relatively widespread in cultivation.

Nepenthes rajah is most famous for the giant urn-shaped traps it produces, which can grow up to 35 cm high and 18 cm wide.[4] These are capable of holding 3.5 litres of water[5] and in excess of 2.5 litres of digestive fluid, making them probably the largest in the genus by volume. Another morphological feature of N. rajah is the peltate leaf attachment of the lamina and tendril, which is present in only a few other species.

The plant is known to occasionally trap vertebrates and even small mammals, with drowned rats having been observed in the pitcher-shaped traps.[6] It is one of only two Nepenthes species documented as having caught mammalian prey in the wild, the other being N. rafflesiana. N. rajah is also known to occasionally trap small vertebrates such as frogs, lizards and even birds, although these cases probably involve sick animals and certainly do not represent the norm. Insects, and particularly ants, comprise the staple prey in both aerial and terrestrial pitchers.

Although Nepenthes rajah is most famous for trapping and digesting animals, its pitchers are also host to a large number of other organisms, which are thought to form a mutually beneficial (symbiotic) association with the plant. Many of these animals are so specialised that they cannot survive anywhere else, and are referred to as nepenthebionts. N. rajah has two such mosquito taxa named after it: Culex rajah and Toxorhynchites rajah.

Another key feature of N. rajah is the relative ease with which it is able to hybridise in the wild. Hybrids between it and all other Nepenthes species on Mount Kinabalu have been recorded. However, due to the slow-growing nature of N. rajah, few hybrids involving the species have been artificially produced as of yet.

Contents |

Etymology

Joseph Dalton Hooker described Nepenthes rajah in 1859, naming it in honour of Sir James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak.[7] In the past, the Latin name was written as Nepenthes Rajah,[3][8][9][10][11] since it derives from a proper noun. However, this capitalisation is considered incorrect today. 'Rajah Brooke's Pitcher Plant'[12] is an accurate, but seldom-used common name. N. rajah is also sometimes called the 'Giant Malaysian Pitcher Plant'[13] or simply 'Giant Pitcher Plant', although the binomial name remains by far the most popular way of referring to this species. The specific epithet rajah means "King" in Malay and this, coupled with the impressive size of its pitchers, has meant that N. rajah is often referred to as the "King of Nepenthes".[14]

Plant characteristics

Latin description: Folia mediocria petiolata, lamina oblonga v. lanceolata, apice peltata, nervis longitudinalibus utrinque 4–5 ; ascidia rosularum ignota; ascidia inferiora et superiora maxima, urceolata, alis 2 subfimbriatis, ore maximo obliquo; peristomio in collum breve elongato, expanso, 10–30 mm lato, costis 1/2–2 distantibus, dentibus 2–4 x longioribus quam latis; operculo maximo ovato-cordato, facie inferiore prope basin carina valida exaltata; inflorescentia racemus magnus pedicellis inferioribus c. 20–25 mm longis 2-floris, superioribus brevioribus 1-floris ; indumentum parcum, villosum v. villoso-tomentosum.[11]

Botanical description: Stem: generally prostrate or decumbent; not climbing, coarse, 15–30 mm thick, ≤6 m long (usually ≤3 m), yellow to green in colour, internodes ≤20 cm, cylindrical. Leaves: coriaceous, shortly petiolate, yellow to green in colour, with a wavy outer margin. Lamina oblong-lanceolate, 25–80 cm long and 10–15 cm wide, rounded and peltate at the apex, rounded at the base, abruptly attenuate towards the petiole. Tendril inserted 2–5 cm below the leaf apex. Petiole canaliculate, winged, ≤15 cm long, ≤1 cm thick, dilated at the base, with a sheath that clasps the stem for 3/4 of the circumference. Longitudinal veins 3–4 (rarely 5) on each side, originating from the basal part of the midrib, running parallel in the outer half of the lamina, pennate veins running obliquely towards the margin, irregularly reticulate in the outer part of the lamina. Tendrils about as long as the lamina, ≤50 cm long, 5–6 mm thick near the lamina, 10–25 mm thick near the pitcher, curved downwards, yellow to red in colour, darker near the pitcher. Pitchers: urceolate to short-ellipsoidal, 20–40 cm high, 11–18 cm wide, red to purple on the outside, inside surfaces lime green to purple in colour, with two fimbriate wings running almost from the base to the mouth, broader and more fimbriate towards the top, 6–25 mm wide under the mouth, the fringe segments ≤7 mm long, 2–4 mm apart. Glandular region covers the entire inner surface of the pitcher, about 300–800 glands/cm², the glands in the lower part (digestive zone) not overarched, large such that the interspaces only form polygons, overarched in the upper half (conductive/retentive zone). Mouth horizontal to oblique, the front side of the pitcher 1/2 to 2/5 of the back side in length, elongated towards the lid into a neck 2.5–4 cm long. Peristome greatly expanded, 10–15 mm wide at the front side, 20–50 mm wide towards the lid, distinctly scalloped, prolongated at the interior side into a perpendicular lamina that is 10–20 mm wide, the ribs 0.5–1 mm apart at the inner side, 1–2 mm apart at the outer margin, teeth distinct, those of the interior margin 2 to 4 times as long as broad. Lid ovate to oblong, rounded at the apex, cordate at the base, 15–25 cm long, 11–20 cm wide, vaulted with a distinct keel running down the centre, midrib keeled in the basal half below, keel 5–10 mm high at some distance from the base, 3–8 mm wide, no appendages. Lower surface of the lid covered in many elevated glands, those on the keel with a wide mouth, the others with a very narrow one. Spur ≤20 mm long, unbranched, ascending from the back rib of the pitcher close to the lid, about 2 mm thick at the base, attenuate. Intermediate and upper pitchers rarely produced, conical, smaller, lighter in colour; usually yellow, wings reduced to ribs. Male inflorescence: a long raceme, peduncle 20–40 cm long, about 10 mm thick at the base, about 7 mm at the top, cylindrical, yellow-green to orange in colour, the rachis 30–80 cm long, angular and grooved, gradually attenuate. Lower partial peduncles 20–25 mm long, two-flowered, upper ones gradually shorter, one-flowered, all without bract. Flowers brownish-yellow in colour, give off strong sugary smell. Tepals elliptic to oblong, ≤8 mm long, obtuse, burgundy in colour. Staminal column 3–4 mm long, anthers in 1 of 1 1/2 whorls. Female inflorescence: generally like male inflorescence, but the tepals are somewhat narrower. Fruits short-pedicelled, 10–20 mm long, relatively thick, slightly attenuate towards both ends, orange-brown in colour, the valves 2.5–4 mm wide. Seeds filiform, 3–8 mm long, nucleus only slightly wrinkled, if at all. Indumentum: all parts of the plant covered with long, caducous, white or brown hairs when young, mature plants virtually glabrous. Stem with long spreading brown hairs when young, later glabrous. Pitchers densely covered with long spreading brown hairs when young, later sparsely hairy or glabrous. Inflorescences densely covered with adpressed brown hairs when young, later more sparsely hairy in the lower part, indumentum persistent in the upper part on the peduncles and on the perigone, ovaries densely appressedly hairy, fruits less densely hairy to glabrous. Other: colour of herbarium specimens dark-brown in varying hues.[11][15]

Nepenthes rajah, like virtually all species in the genus, is a scrambling vine. The stem usually grows along the ground, but will attempt to climb whenever it comes into contact with an object that can support it. The stem is relatively thick (≤30 mm) and may reach up to 6 m in length, although it rarely exceeds 3 m.[16] N. rajah does not produce runners as some other species in the genus, but older plants are known to form basal offshoots. This is especially common in plants from tissue culture, where numerous offshoots may form at a young age.

Leaves

Leaves are produced at regular intervals along the stem. They are connected to the stem by sheathed structures known as petioles. A long, narrow tendril emanates from the end of each leaf. At the tip of the tendril is a small bud which, when physiologically activated, develops into a functioning trap. Hence, the pitchers are modified leaves and not specialised flowers as is often believed. The green structure most similar to a normal leaf is specifically known as the lamina or leaf blade.

The leaves of N. rajah are very distinctive and reach a large size. They are leathery in texture with a wavy outer margin. The leaves are characteristically peltate, whereby the tendril joins the lamina on the underside, before the apex. This characteristic is more pronounced in N. rajah than in any other Nepenthes species, with the exception of N. clipeata. However, it is not unique to these two taxa, as mature plants of many Nepenthes species display slightly peltate leaves. The tendrils are inserted ≤5 cm below the leaf apex and reach a length of approximately 50 cm.[15] Three to five longitudinal veins run along each side of the lamina and pennate (branching) veins run towards the margin. The lamina is oblong to lanceolate-shaped, ≤80 cm long and ≤15 cm wide.

Pitchers

All Nepenthes pitchers share several basic characteristics. Traps consist of the main pitcher cup, which is covered by an operculum or lid that prevents rainwater from entering the pitcher and displacing or diluting its contents. A reflexed ring of hardened tissue, known as the peristome, surrounds the entrance to the pitcher (only the aerial pitchers of N. inermis lack a peristome). A pair of fringed wings run down the front of lower traps and these presumably serve to guide terrestrial insects into the pitchers' mouth. Accordingly, the wings are greatly reduced or completely lacking in aerial pitchers, for which flying insects constitute the majority of prey items.

N. rajah, like most species in the genus, produces two distinct types of traps. "Lower" or "terrestrial" pitchers are the most common. These are very large, richly coloured, and ovoid in shape. In lower pitchers, the tendril attachment occurs at the front of the pitcher cup relative to the peristome and wings. Exceptional specimens may be up to 40 cm high and capable of holding 3.5 litres of water[5] and in excess of 2.5 litres of digestive fluid, although most do not exceed 200 ml.[17] The lower pitchers of N. rajah are probably the largest in the genus by volume, rivaled only by those of N. merrilliana, N. truncata and the giant form of N. rafflesiana. These traps rest on the ground and are often reclined, leaning against surrounding objects for support. They are usually red to purple on the outside, whilst the inside surfaces are lime green to purple. This contrasts with all other parts of the plant, which are yellow-green. The lower pitchers of N. rajah are unmistakable and for this reason it is easy to distinguish it from all other Bornean Nepenthes species.[18]

Mature plants may also produce "upper" or "aerial" pitchers, which are much smaller, funnel-shaped, and usually less colourful than the lowers. The tendril attachment in upper pitchers is normally present at the rear of the pitcher cup. True upper pitchers are seldom seen, as the stems of N. rajah rarely attain lengths greater than a few metres before dying off and being replaced by off-shoots from the main rootstock.[19]

Upper and lower pitchers differ significantly in morphology, as they are specialised for attracting and capturing different prey. Pitchers that do not fall directly into either category are simply known as "intermediate" pitchers.

The peristome of N. rajah has a highly distinctive scalloped edge and is greatly expanded, forming an attractive red lip around the trap's mouth. A series of raised protrusions, known as ribs, intersect the peristome, ending in short, sharp teeth that line its inner margin. Two fringed wings run from the tendril attachment to the lower edge of the peristome.

The huge, vaulted lid of N. rajah, the largest in the genus, is another distinguishing characteristic of this species. It is ovate to oblong in shape and has a distinct keel running down the middle. The spur at the back of the lid is approximately 20 mm long and unbranched.[4]

N. rajah is noted for having very large nectar-secreting glands covering its pitchers. These are quite different from those of any other Nepenthes and are easily recognisable (see image). The inner surface of the pitcher, in particular, is wholly glandular, with 300 to 800 glands/cm².[11]

Flowers

N. rajah seems to flower at any time of the year. Flowers are produced in large numbers on inflorescences that arise from the apex of the main stem. N. rajah produces a very large inflorescence that can be 80 cm, and sometimes even 120 cm tall.[4][5] The individual flowers of N. rajah are produced on partial peduncles (twin stalks) and so the inflorescence is called a raceme (as opposed to a panicle for multi-flowered bunches). The flowers are reported to give off a strong sugary smell and are brownish-yellow in colour. Sepals are elliptic to oblong and ≤8 mm long.[4] Like all Nepenthes species, N. rajah is dioecious, which means that unisexual flowers occur on different individuals. Fruits are orange-brown and 10 to 20 mm long (see image).

Other characteristics

The root system of N. rajah is notably extensive, although it is relatively shallow as in most Nepenthes species.

All parts of the plant are covered in long, white hairs when young, but mature plants are virtually glabrous (lacking hair). This covering of hair is known as the indumentum.

The colour of herbarium specimens is dark-brown in varying hues (see image).

Little variation has been observed within natural populations of Nepenthes rajah and, consequently, no forms or varieties have been described. Furthermore, N. rajah has no true nomenclatural synonyms,[20] unlike many other Nepenthes species, which exhibit greater variability.

Carnivory

- See also: Pitfall traps

Nepenthes rajah is a carnivorous plant of the pitfall trap variety. It is famous for occasionally trapping vertebrates and even small mammals. There exist at least two records of drowned rats found in N. rajah pitchers. The first observation dates from 1862 and was made by Spenser St. John, who accompanied Hugh Low on two ascents of Mount Kinabalu.[14] In 1988, Anthea Phillipps and Anthony Lamb confirmed the plausibility of this record when they managed to observe drowned rats in a large pitcher of N. rajah.[6][14]

N. rajah is also known to occasionally trap other small vertebrates, including frogs, lizards and even birds, although these cases probably involve sick animals, or those seeking shelter or water in the pitcher, and certainly do not represent the norm.[21] Insects, and particularly ants, comprise the majority of prey in both aerial and terrestrial pitchers.[17] Other arthropods, such as centipedes, also fall prey to N. rajah.

N. rajah has evolved a mutualistic relationship with Mountain Treeshrews in order to collect their droppings. The inside of the pitchers exude a sweet nectar. The distance from the pitcher mouth to the exudate is the same as the average body length of the Mountain Treeshrew. These proportions also hold true for N. lowii and N. macrophylla. As it feeds the treeshew defecates, apparently as a method of marking its feeding territory. It is thought that in exchange for providing nectar, the feces provides N. rajah with the majority of the nitrogen it requires.[22][23]

N. rafflesiana is the only other Nepenthes species reliably documented as having caught mammalian prey in its natural habitat. In Brunei, frogs, geckos and skinks have been found in the pitchers of this species.[21][24] The remains of mice have also been reported.[25] On September 29, 2006, at the Jardin botanique de Lyon in France, a cultivated N. truncata was photographed containing the decomposing corpse of a mouse.[26]

Interactions with animals

Pitcher infauna

Although Nepenthes are most famous for trapping and digesting animals, their pitchers also play host to a large number of other organisms (known as infauna). These include fly and midge larvae, spiders (most notably the crab spider Misumenops nepenthicola), mites, ants, and even a species of crab, Geosesarma malayanum. The most common and conspicuous predators found in pitchers are mosquito larvae, which consume large numbers of other larvae during their development. Many of these animals are so specialised that they cannot survive anywhere else, and are referred to as nepenthebionts.[27]

The complex relationships between these various organisms are not yet fully understood. The question of whether infaunal animals "steal" food from their hosts, or whether they are involved in a mutually beneficial (symbiotic) association has yet to be investigated experimentally and is the source of considerable debate. Clarke suggests that mutualism is a "likely situation", whereby "the infauna receives domicile, protection and food from the plant, while in return, the infauna helps to break down the prey, increase the rate of digestion and keep bacterial numbers low".[28]

Species specific

As the size and shape of Nepenthes pitchers vary greatly between species, but little within a given taxon, it is not surprising that many infaunal organisms are specially adapted to life in only the traps of particular species. N. rajah is no exception, and in fact has two mosquito taxa named after it. Culex (Culiciomyia) rajah and Toxorhynchites (Toxorhynchites) rajah were described by Masuhisa Tsukamoto in 1989, based on larvae collected in pitchers of N. rajah on Mount Kinabalu three years earlier.[29] The two species were found to live in association with larvae of Culex (Lophoceraomyia) jenseni, Uranotaenia (Pseudoficalbia) moultoni and an undescribed taxon, Tripteroides (Rachionotomyia) sp. No. 2. Concerning C. rajah, Tsukamoto noted that the "body surface of most larvae are covered in Vorticella-like protozoa".[30] At present, nothing is known of this species with regards to its adult biology, habitat, or medical importance as a vector of diseases. The same is true for T. rajah; nothing is known of its biology except that adults are not haematophagous.

Another species, Culex shebbearei, has also been recorded as an infaunal organism of N. rajah in the past. The original 1931 record by F. W. Edwards[31] is based on a collection by H. M. Pendlebury in 1929 from a plant growing on Mount Kinabalu. However, Tsukamoto notes that in light of new information on these species, "it seems more likely to conclude that the species [C. rajah] is a new species which has been misidentitied as C. shebbearei for a long time, rather than to think that both C. shebbearei and C. rajah n. sp. are living in pitchers of Nepenthes rajah on Mt. Kinabalu".[30]

Pests

Not all interactions between Nepenthes and fauna are beneficial to the plant. N. rajah is sometimes attacked by insects which feed on its leaves and remove substantial portions of the lamina. Also, monkeys and tarsiers are known to occasionally rip pitchers open to feed on their contents.[32]

History and popularity

Due to its size, unusual morphology and striking colouration, N. rajah has always been a very popular and highly sought-after insectivorous plant. However, despite its popularity amongst pitcher plant enthusiasts, it is fair to say that Nepenthes rajah remains a little known species outside the field of carnivorous plants. Due to its specialised growing requirements, it is not a suitable candidate for a houseplant and, as such, is only cultivated by a relatively small number of hobbyists and professional growers worldwide. This being the case, N. rajah is nonetheless probably the most famous of all pitcher plants. Its reputation for producing some of the most magnificent pitchers in the genus dates back to the late 18th century.

N. rajah was first collected by Hugh Low on Mount Kinabalu in 1858.[12] It was described the following year by Joseph Dalton Hooker, who named it after James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak. The description was published in The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London:[3]

Nepenthes Rajah, H. f. (Frutex, 4-pedalis, Low). Foliis maximis 2-pedalibus, oblongo-lanceolatis petiolo costaque crassissimis, ascidiis giganteis (cum operculo l-2-pedalibus) ampullaceis ore contracto, stipite folio peltatim affixo, annulo maximo lato everso crebre lamellato, operculo amplissimo ovato-cordato, ascidium totum æquante.—(Tab. LXXII.) Hab.—Borneo, north coast, on Kina Balu, alt. 5,000 feet (Low). This wonderful plant is certainly one of the most striking vegetable productions hitherto discovered, and, in this respect, is worthy of taking place side by side with the Rafflesia Arnoldii. It hence bears the title of my friend Rajah Brooke, of whose services, in its native place, it may be commemorative among botanists. . . . I have only two specimens of leaves and pitchers, both quite similar, but one twice as large as the other. Of these, the leaf of the larger is 18 inches long, exclusive of the petioles, which is as thick as the thumb and 7–8 broad, very coriaceous and glabrous, with indistinct nerves. The stipes of the pitcher is given off below the apex of the leaf, is 20 inches long, and as thick as the finger. The broad ampullaceous pitcher is 6 inches in diameter, and 12 long: it has two fimbriated wings in front, is covered with long rusty hairs above, is wholly studded with glands within, and the broad annulus is everted, and 1–1½ inch in diameter. Operculum shortly stipitate, 10 inches long and 8 broad. The inflorescence is hardly in proportion. Male raceme, 30 inches long, of which 20 are occupied by the flowers; upper part and flowers clothed with short rusty pubescence. Peduncles slender, simple or bifid. Fruiting raceme stout. Peduncles 1½ inches long, often bifid. Capsule, ¾ inch long, ⅓ broad, rather turgid, densely covered with rusty tomentum.

Spenser St. John wrote the following account of his encounter with N. rajah on Mount Kinabalu in Life in the Forests of the Far East published in 1862:[33]

Another steep climb of 800 feet brought us to the Marei Parei spur, to the spot where the ground was covered with the magnificent pitcher-plants, of which we had come in search. This one has been called the Nepenthes Rajah, and is a plant about four feet in length, with broad leaves stretching on every side, having the great pitchers resting on the ground in a circle about it. Their shape and size are remarkable. I will give the measurement of one, to indicate the form: the length along the back nearly fourteen inches; from the base to the top of the column in front, five inches; and its lid a foot long by fourteen inches broad, and of an oval shape. Its mouth was surrounded by a plaited pile, which near the column was two inches broad, lessening in its narrowest part to three-quarters of an inch. The plaited pile of the mouth was also undulating in broad waves. Near the stem the pitcher is four inches deep, so that the mouth is situated upon it in a triangular manner. The colour of an old chalice is a deep purple, but that of the others is generally mauve outside, very dark indeed in the lower part, though lighter towards the rim; the inside is of the same colour, but has a kind of glazed and shiny appearance. The lid is mauve in the centre, shading to green at the edges. The stems of the female flowers we found always a foot shorter than those of the male, and the former were far less numerous than the latter. It is indeed one of the most astonishing productions of nature. [...] The pitchers, as I have before observed, rest on the ground in a circle, and the young plants have cups of the same form as those of the old ones. While the men were cooking their rice, we sat before the tent enjoying our chocolate and observing one of our followers carrying water in a splendid specimen of the Nepenthes Rajah, desired him to bring it to us, and found that it held exactly four pint bottles. It was 19 inches in circumference. We afterwards saw others apparently much larger, and Mr. Low, while wandering in search of flowers, came upon one in which was a drowned rat.

N. rajah was first collected for the Veitch Nurseries by Frederick William Burbidge in 1878, during his second trip to Borneo.[34] Shortly after being introduced into cultivation in 1881, N. rajah proved very popular among wealthy Victorian horticulturalists and became a much sought-after species. A note in The Gardeners' Chronicle of 1881 mentions the Veitch plant as follows: "N. rajah at present is only a young Rajah, what it will become was lately illustrated in our columns...".[35] A year later, young N. rajah plants were displayed at the Royal Horticultural Society's annual show for the first time.[36] The specimen exhibited at the show by the Veitch Nurseries, the first of this species to be cultivated in Europe, won a first class certificate.[37] In Veitch's catalogue for 1889, N. rajah was priced at £2.2s per plant.[38] During this time, interest in Nepenthes had reached its peak. The Garden reported that Nepenthes were being propagated by the thousands to keep up with European demand.

However, dwindling interest in Nepenthes at the turn of the century saw the demise of the Veitch Nurseries and consequently the loss of several species and hybrids in cultivation, including N. northiana and N. rajah. By 1905, the final N. rajah specimens from the Veitch nurseries were gone, as the cultural requirements of the plants proved too difficult to reproduce.[36] The last surviving N. rajah in cultivation at this time was located at the National Botanic Gardens at Glasnevin in Ireland, however this soon perished also.[36] It would be many years until N. rajah was reintroduced into cultivation.

Early publications: Transact. Linn. Soc., XXII, p. 421 t. LXXII (1859) ; MIQ., Ill., p. 8 (1870) ; HOOK. F., in D.C., Prodr., XVII, p. 95 (1873) ; MAST., Gard. Chron., 1881, 2, p. 492 (1881) ; BURB., Gard. Chron., 1882, 1, p. 56 (1882) ; REG., Gartenfl., XXXII, p. 213, ic. p. 214 (1883) ; BECC., Mal., III, p. 3 & 8 (1886) ; WUNSCHM., in ENGL. & PRANTL, Nat. Pflanzenfam., III, 2, p. 260 (1891) ; STAPF, Transact. Linn. Soc., ser. 2, bot., IV, p. 217 (1894) ; BECK, Wien. Ill. Gartenz., 1895, p. 142, ic. 1 (1895) ; MOTT., Dict., III, p. 451 (1896) ; VEITCH, Journ. Roy. Hort. Soc., XXI, p. 234 (1897) ; BOERL., Handl., III, 1, p. 54 (1900) ; HEMSL., Bot. Mag., t. 8017 (1905) ; Gard. Chron., 1905, 2, p. 241 (1905) ; MACF., in ENGL., Pflanzenr., IV, 111, p. 46 (1908) ; in BAIL., Cycl., IV, p. 2129, ic. 2462, 3 (1919) ; MERR., Bibl. Enum. Born., p. 284 (1921) ; DANS., Trop. Nat., XVI, p. 202, ic. 7 (1927).[11]

Early illustrations: Transact. Linn. Soc., XXII, t. LXXII (1859) optima; Gard. Chron., 1881, 2, p. 493 (1881) bona, asc. 1 ; Gartenfl., 1883, p. 214 (1883) bona, asc. 1 ; Wien. Ill. Gartenfl., 1895, p. 143, ic. 1 (1895) asc. 1 ; Journ. Roy. Hort. Soc., XXI, p. 228 (1897) optima; Bot. Mag., t. 8017 (1905) optima; BAIL., Cycl., IV, ic. 2462, 3 (1919) asc. 1 ; Trop. Nat., XVI, p. 203 (1927) asc. 1.[11]

Early collections: North Borneo. Mt. Kinabalu, IX 1913, Herbarium of the Sarawak Museum (material without flowers or fruits) ; Marai-parai Spur, 1-4 XII 1915, Clemens 11073, Herbarium Bogoriense, the Herbarium of the Buitenzorg Botanic Gardens (male and female material) ; 1650 m, 1892, Haviland 1812/1852, Herbarium of the Sarawak Museum (male and female material).[11]

Recent popularity

In recent years there has been renewed interest in Nepenthes worldwide. Much of the plants' current popularity can probably be attributed to Shigeo Kurata, whose book Nepenthes of Mount Kinabalu (1976), which featured the best colour photography of Nepenthes to date, did much to bring attention to these unusual plants.

Not surprisingly, N. rajah is a relatively well known plant in Malaysia, especially its native Sabah. The species is often used to promote Sabah, and specifically Kinabalu National Park, as a tourist destination, and features prominently on postcards from the region. Nepenthes rajah has appeared on the covers of several popular Nepenthes publications, including Nepenthes of Mount Kinabalu (Kurata, 1976) and Nepenthes of Borneo (Clarke, 1997), both published in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia. On April 6, 1996, Malaysia issued a series of four postage stamps depicting some of its more famous Nepenthes species. Two 30¢ stamps, featuring N. macfarlanei and N. sanguinea, as well as two 50¢ stamps, depicting N. lowii and N. rajah, were released.[39] The N. rajah stamp has been assigned a unique identification number in two popular stamp numbering systems. These are Scott #580 and Yvert #600. Curiously, the peltate leaf attachment that is so characteristic of this species is not shown.

Classification

|

|

||||||||

| N. maxima | N. pilosa | N. clipeata | ||||||

| N. oblanceolata * | N. burbidgeae | N. truncata | ||||||

| N. veitchii | N. rajah | N. fusca | ||||||

| N. ephippiata | N. boschiana | N. stenophylla ** | ||||||

| N. klossii | N. mollis | N. lowii | ||||||

|

* Now considered a junior synonym of N. maxima.

** Danser's description was based on the type specimen of N. fallax. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Distribution of the Regiae, based on Danser (1928).

Note: it is now known that N. maxima is absent from Borneo. |

||||||||

Nepenthes rajah is not generally considered to be closely related to any other species, due to its unusual pitcher and leaf morphology. However, several attempts have been made to deduce natural groupings within the Nepenthes genus, in order to show relationships between taxa below those at the genus rank, which have grouped N. rajah with other species thought to share certain traits with it.

The Nepenthes were first split up in 1873, when Hooker published his monograph on the genus. Hooker distinguished N. pervillei from all other taxa based on the fact that seeds of this species lacked appendages that were found to be present in all other Nepenthes (though greatly reduced in N. madagascariensis) and subsequently placed it in the monotypic subgenus Anurosperma (Latin: anuro: without nerves, sperma: seeds). All other species were subsumed in the second subgenus, Eunepenthes (Latin: eu: true; "true" Nepenthes).

A second attempt to establish a natural subdivision within the genus was made in 1895 by Günther von Mannagetta und Lërchenau Beck in his Monographische Skizze (German for Monographic Sketch).[40] Beck kept the two subgenera created by Hooker, but divided Eunepenthes into three subgroups: Retiferae, Apruinosae and Pruinosae. N. rajah formed part of the Apruinosae (Latin: pl. of apruinosa: not frosted). Most contemporary taxonomists agree that Beck's groupings have little, if any, taxonomical value, as they were based on arbitrary traits not suitable for use as a basis for classification.

Nepenthes taxonomy was once again revised in 1908 by John Muirhead Macfarlane in his own monograph.[41] Oddly, Macfarlane did not name the groups he distinguished. His revision is often not considered to be a natural division of the genus.

In 1928, B. H. Danser published his seminal monograph, The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies, in which he divided Nepenthes into six clades, based on observations of herbarium material.[42] The clades were: the Vulgatae, Montanae, Nobiles, Regiae, Insignes and Urceolatae. Danser placed N. rajah in the Regiae (Latin: pl. of rēgia: royal). The Regiae clade as proposed by Danser is shown in the table to the right.

Most of the species in this clade are large plants with petiolate leaves, an indumentum of coarse reddish-brown hairs, raceme-like inflorescence, and funnel-shaped (infundibulate) upper pitchers. All bear a characteristic appendage on the lower surface of the lid near the apex. With the exception of N. lowii, the Regiae all have a mostly flattened or expanded peristome. The majority of species comprising Regiae are endemic to Borneo. Based on current understanding of the genus, Regiae appears to reflect the relationships of its members quite well, although the same cannot be said for the other clades.[43] Despite this, Danser's classification was undoubtedly a great improvement on previous attempts.

The taxonomical work of Danser (1928) was revised by Hermann Harms in 1936. Harms divided Nepenthes into three subgenera: Anurosperma Hooker.f. (1873), Eunepenthes Hooker.f. (1873) and Mesonepenthes Harms (1936) (Latin: meso: middle; "middle" Nepenthes). The Nepenthes species found in the subgenera Anurosperma and Mesonepenthes differ from those in the Vulgatae, where Danser had placed them. Harms included N. rajah in the subgenus Eunepenthes together with the great majority of other Nepenthes; Anurosperma was a monotypic subgenus, while Mesonepenthes contained only three species. He also created an additional clade, the Distillatoriae (after N. distillatoria).

In 1976, Shigeo Kurata proposed that glands present in Nepenthes pitchers were unique to individual species and could be used to distinguish between closely-related taxa or even be used as a basis for their classification. Kurata studied two types: the nectar glands of the lid and the digestive glands of the inside of the pitcher cup. He divided the latter into the "lower", "upper" and "middle" parts. Although this novel approach shed additional light on the similarities between certain species, it has since been largely abandoned by taxonomists and botanists specialising in the genus, in favour of classical taxonomical nomenclature based on a description of morphological characters.

| Distribution of phenolic compounds and leucoanthocyanins in N. × alisaputrana, N. burbidgeae and N. rajah | |||||||||

| Taxon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Specimen |

| N. × alisaputrana |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

J2442 |

| in vitro |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N. burbidgeae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

J2484 |

| N. rajah |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

J2443 |

| Key: 1: Phenolic acid, 2: Ellagic acid, 3: Quercetin, 4: Kaempferol, 5: Luteolin, 6: 'Unknown Flavonoid 1', 7: 'Unknown Flavonoid 3', 8: Cyanidin

±: very weak spot, +: weak spot, ++: strong spot, 3+: very strong spot, -: absent, J = Jumaat Source: OnLine Journal of Biological Sciences 2 (9): 623–625.PDF |

|||||||||

Biochemical analysis

More recently, biochemical analysis has been used as a means to determine cladistical relationships between Nepenthes species. In 1975, David E. Fairbrothers et al.[44] first suggested a link between chemical properties and certain morphological groupings, based on the theory that morphologically similar plants produce chemical constituents with similar therapeutic effects.[45]

In 2002, phytochemical screening and analytical chromatography were used to study the presence of phenolic compounds and leucoanthocyanins in several naturally-occurring hybrids and their putative parental species (including N. rajah) from Sabah and Sarawak.[45] The research was based on leaf material from nine dry herbarium specimens. Eight spots containing phenolic acids, flavonols, flavones, leucoanthocyanins and 'unknown flavonoid' 1 and 3 were identified from chromatographic profiles. The distributions of these in the hybrid N. × alisaputrana and its putative parental species N. rajah and N. burbidgeae are shown in the table to the left. A specimen of N. × alisaputrana grown from tissue culture (in vitro) was also tested.

Phenolic and ellagic acids were undetected in N. rajah, while concentrations of kaempferol were found to be very weak. Chromatographic patterns of the N. × alisaputrana samples studied showed complementation of its putative parental species.[45]

Myricetin was found to be absent from all studied taxa. This agrees with the findings of previous authors (R. M. Som in 1988; M. Jay and P. Lebreton in 1972)[46][47] and suggests that the absence of a widely distributed compound like myricetin among the Nepenthes examined might provide "additional diagnostic information for these six species".[48]

Several proteins and nucleotides of N. rajah have been either partially or completely sequenced. These are as follows:

- translocated tRNA-Lys (trnK) pseudogene (DQ007139)[49]

- trnK gene & maturase K (matK) gene (AF315879)[50]

- trnK gene & maturase K (matK) gene (AF315880)[50]

- maturase K (AAK56010)[50]

- maturase K (AAK56011)[50]

Related species

In 1998, a striking new species of Nepenthes was discovered in the Philippines by Andreas Wistuba. Temporarily dubbed N. sp. Palawan 1, it bears a close resemblance to N. rajah in terms of pitcher and leaf morphology.[1][2][3] Due to the geographic distance separating the two species, it is unlikely they are in any way closely related. Thus, this case might represent an example of convergent evolution, whereby two organisms not closely related independently acquire similar characteristics while evolving in separate, but comparable, ecosystems. In 2007, the species was described by Wistuba and Joachim Nerz as N. mantalingajanensis.[51]

Ecology

Kinabalu

Nepenthes rajah has a very localised distribution, being restricted to Mount Kinabalu and neighbouring Mount Tambuyukon, both located in Kinabalu National Park, Sabah, Malaysian Borneo.[2] Mount Kinabalu is a massive granitic dome structure that is geologically young and formed from the intrusion and uplift of a granitic batholith. At 4095.2 m, it is by far the tallest mountain on the island of Borneo and one of the highest peaks in Southeast Asia.[52] The lower slopes of the mountain are mainly composed of sandstone and shale, transformed from marine sand and mud about 35 million years ago. Intrusive ultramafic (serpentine) rock was uplifted with the core of the batholith and forms a collar around the mountain. It is on these ultramafic soils that the flora of Mount Kinabalu exhibits the greatest levels of endemicity and many of the area's rarest species can be found here.

Substrate

N. rajah seems to grow exclusively on serpentine soils containing high concentrations of nickel and chromium, which are toxic to many plant species.[13] Its tolerance of these, therefore, means that it can grow in an ecological niche where it faces less competition for space and nutrients.[53] The root systems of N. × alisaputrana[54] and N. villosa[55] are also known to be resistant to the heavy metals present in serpentine substrates. These soils are also rich in magnesium and are slightly alkaline as a result. They often form a relatively thin layer over a base of ultramafic rock and are thus known as ultramafic soils. Ultramafic soils are thought to cover approximately 16% of Kinabalu National Park. These soils have high levels of endemicity in many taxonomic groups, not least the Nepenthes. Four species in the genus, including N. rajah, can only be found within the boundaries of the park.

N. rajah usually grows in open, grassy clearings on old land slips and flat ridge tops, particularly in areas of seeping ground water, where the soil is loose and permanently moist. Although these sites can receive very high rainfall, excess water drains away quickly, preventing the soil from becoming waterlogged. N. rajah can often be found growing in grassy undergrowth, especially among sedges.

Climate

N. rajah has an altitudinal distribution of 1500–2650 m a.s.l.[7][20] and is thus considered an (ultra) highland or Upper Montane plant.[56] In the upper limit of its range, night-time temperatures may approach freezing and day-time maximums rarely exceed 25 ℃.[57] Due to the night-time temperature drop, relative air humidity increases significantly, rising from 65–75% to over 95%. Vegetation at this height is very stunted and slow-growing due to the extreme environmental conditions that prevail. Plants are often subjected to fierce winds and driving rain, as well as exposure to intense direct sunlight. The relatively open vegetation of the Upper Montane forest also experiences greater fluctuations in temperature and humidity compared with lower altitudes. These changes are largely governed by the extent of cloud cover. In the absence of clouds, temperatures rise rapidly, humidity drops, and light levels may be very high. When cloud cover returns, temperatures and light levels fall, while humidity levels increase.[58] Average annual precipitation in this region is around 3000 mm.

Conservation status

Endangered species

Nepenthes rajah is classified as Endangered (EN – B1+2e) on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1] It is also listed on Schedule I, Part II of the Wildlife Conservation Enactment (WCE) 1997[59] and, perhaps more notably, CITES Appendix I,[60] which prohibits international trade in plants collected from the wild. However, due to its popularity among collectors, many plants have been removed from the wild illegally,[61] even though the species' distribution lies entirely within the bounds of Kinabalu Park. This led to some populations being severely depleted by over-collection in the 1970s and eventually resulted in the species' inclusion in CITES Appendix I in 1981.[62] Together with N. khasiana, it is one of only two species in the genus to feature on this list; all other Nepenthes species are covered by Appendix II.

This being the case, however, the short-term future of N. rajah seems to be relatively secure and it would perhaps be more accurately classified as Vulnerable (VU) or, taking into account protected populations in National Parks, Lower Risk conservation dependent (LR (cd)).[63] This agrees with the conservation status of N. rajah according to the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), under which it is also considered Vulnerable. Furthermore, the species was originally treated as Vulnerable (V) by the IUCN prior to the introduction of the 1994 threat categories.

Although N. rajah has a restricted distribution and is often quoted as a plant in peril,[64] it is not rare in the areas where it does grow and most populations are now off-limits to visitors and lie in remote parts of Kinabalu National Park. Furthermore, N. rajah has a distinctive leaf shape making it difficult to illegally ship abroad even if the pitchers are removed, as an informed customs official should be able to identify it.

The recent advent of artificial tissue culture, or more specifically in vitro, technology in Europe and the United States has meant that plants can be produced in large numbers and sold at relatively low prices (~US$20–$30 in the case of N. rajah). In vitro propagation refers to production of whole plants from cell cultures derived from explants (generally seeds). This technology has, to a large extent, removed the incentive for collectors to travel to Sabah to collect the plant illegally, and demand for wild-collected plants has fallen considerably in recent years.[65]

Rob Cantley, a prominent conservationist and artificial propagator of Nepenthes plants, assesses the current status of plants in the wild as follows:[66]

This species grows in at least 2 distinct sub-populations, both of which are well protected by Sabah National Parks Authority. One of the populations grows in an area public access to which is strictly prohibited without permit. However, there has been a decline in population of mature individuals in the better known and less patrolled site. This is largely due to damage to habitat and plants by careless visitors rather than organised collection of plants. Nepenthes rajah has become common in cultivation in recent years as a result of the availability of inexpensive clones from tissue culture. I believe that these days commercial collection of this species from the wild is negligible.

This being the case, however, it appears that the genetic variability of cultivated N. rajah plants is very small, as all commercially available tissue-cultured plants are thought to belong to just four clones originating from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London, England.

However, illegal collection is not the only threat facing plants in the wild. The El Niño climatic phenomenon of 1997/98 had a catastrophic effect on the Nepenthes species on Mount Kinabalu.[67] The dry period that followed severely depleted some natural populations. Forest fires broke out in 9 locations in Kinabalu Park, covering a total area of 25 square kilometres and generating large amounts of smog. During the El Niño period, many plants were temporarily transferred to the park nursery to save at least some individuals. These were later replanted in the "Nepenthes Garden" in Mesilau (see below). In spite of this, N. rajah was one of the less affected species and relatively few plants perished as a result. Since then, Ansow Gunsalam has established a nursery close to the Mesilau Lodge at the base of Kinabalu Park to protect the endangered species of that area, including N. rajah.

Restricted distribution

The newly opened Mesilau Nature Resort, which lies near the golf course behind the village of Kundasang, is now the only place where regular visitors can hope to see this species in its natural habitat.[68] Here, several dozen N. rajah plants grow near the top of a steep landslide. Both young and mature plants are present, some with sizable pitchers approaching 35 cm in height (see Image:Rajah3.jpg). Due to their great size, several plants are thought to be over 100 years old. Daily guided tours are organised to the "Nepenthes Garden" where these plants are located. The "Nepenthes rajah Nature Trail", as it is called, is subject to a fee and operates daily from 9:00am to 4:00pm. Almost all other natural populations of this species occur in remote parts of Kinabalu National Park, which are off-limits to tourists.[68] Visitors to the park can also see N. rajah on display in the nursery adjoining the "Mountain Garden" at Kinabalu Park Headquarters.[69]

Other known localities of wild N. rajah populations include the Marai Parai plateau, Mesilau East River near Mesilau Cave, Upper Kolopis River and eastern slope of Mount Tambuyukon.[7]

Natural hybrids

Nepenthes rajah is known to hybridise with several other species with which it is sympatric. It seems to flower at any time of year and for this reason it hybridises relatively easily. Charles Clarke also notes that "N. rajah, more than any other species, appears to have been successful in having its pollen transported over considerable distances. Consequently, a number of putative N. rajah hybrids exist without the parent plant growing nearby". However, it appears that the limit as to how far pollen can be transported is approximately 10 km.[70] Hybrids between N. rajah and all other Nepenthes species on Mount Kinabalu have been recorded.[2][71] Due to the slow-growing nature of N. rajah, few hybrids involving it have been artificially produced as of yet.

At present, the following natural hybrids are known:[20]

- N. burbidgeae × N. rajah [=N. × alisaputrana J.H.Adam & Wilcock (1992)]

- N. edwardsiana × N. rajah

- N. fusca × N. rajah

- N. lowii × N. rajah[71]

- N. macrovulgaris × N. rajah

- N. rajah × N. stenophylla

- N. rajah × N. tentaculata

- N. rajah × N. villosa [=N. × kinabaluensis Sh.Kurata (1976) nom.nud.]

The "Mountain Garden" of Kinabalu National Park contains a number of well-grown Nepenthes, including the rare hybrid N. rajah × N. stenophylla. This plant has leaves resembling those of N. stenophylla, but the lid and wings are typical of N. rajah. The peristome is strongly influenced by N. stenophylla and bristles are present at the border of the lid, a unique characteristic of this hybrid.[72] It occurs at an altitude of 1500–2600 m.

Two hybrids of N. rajah have been formally described and given specific names: N. × alisaputrana and N. × kinabaluensis. Both are listed on CITES Appendix II and the latter is also considered Endangered (EN (D)) under current IUCN criteria.[73]

Nepenthes × alisaputrana

N. × alisaputrana (originally published as "Nepenthes × alisaputraiana")[74] is named in honour of Datuk Lamri Ali, Director of Sabah Parks. It is only known from a few remote localities within Kinabalu National Park where is grows in stunted, open vegetation over serpentine soils at around 2000 m above sea level, often amongst populations of N. burbidgeae. This plant is notable for combining the best characters of both parent species, not least the size of its pitchers, which rival those of N. rajah in volume (≤35 cm high, ≤20 cm wide).[75] The other hybrids involving N. rajah do not exhibit such impressive proportions. The pitchers of N. × alisaputrana can be distinguished from those of N. burbidgeae by a broader peristome, larger lid and simply by their sheer size. The hybrid differs from its other parent, N. rajah, by its lid structure, indumentum of short, brown hairs, narrower and more cylindrical peristome, and pitcher colour, which is usually yellow-green with red or brown flecking. For this reason, Phillipps and Lamb (1996) gave it the common name Leopard pitcher-plant, though this is rarely used. The peristome is green to dark red and striped with purple bands. Leaves are often slightly peltate. The plant climbs well and aerial pitchers are frequently produced. N. × alisaputrana more closely resembles N. rajah than N. burbidgeae, but it is difficult to confuse this plant with either. However, this mistake has previously been made on at least one occasion; a pitcher illustrated in Insect Eating Plants & How To Grow Them (Slack, 1986) as being N. rajah was in fact N. burbidgeae × N. rajah.[76][77]

Nepenthes × kinabaluensis

N. × kinabaluensis is another impressive plant. The pitchers get large also, but do not compare to those of N. rajah or N. × alisaputrana. It is a well-known natural hybrid of what many consider to be the two most spectacular Nepenthes species of Borneo: N. rajah and N. villosa. N. × kinabaluensis can only be found on Mount Kinabalu (hence the name) and nearby Mount Tambuyukon, where the two parent species are occur sympatrically.[78] More specifically, plants are known from a footpath near Paka Cave and several places along an unestablished route on a south-east ridge, which lies on the west side of the Upper Kolopis River.[79] The only accessible location from which this hybrid is known is the Kinabalu summit trail, between Layang-Layang and the helipad, where it grows at about 2900 m in a clearing dominated by Dacrydium gibbsiae and Leptospermum recurvum trees. N. × kinabaluensis has an altitudinal distribution of 2420 to 3030 m.[14] It grows in open areas in cloud forest. This hybrid can be distinguished from N. rajah by the presence of raised ribs that line the inner edge of the peristome and end with elongated teeth. These are more prominent than those found in N. rajah and are clue as to the hybrid's parentage (N. villosa has very developed peristome ribs). The peristome is coarse and expanded at the margin (but not scalloped like that of N. rajah), the lid orbiculate or reniformed and almost flat. In general, pitchers are larger than those of N. villosa and the tendril joins the apex about 1–2 cm below the leaf tip, a feature which is characteristic of N. rajah.[80] In older plants, the tendril can be almost woody. N. × kinabaluensis is an indumentum of villous hairs covering the pitchers and leaf margins, which is approximately intermediate between the parents. Lower pitchers have two fringed wings, whereas the upper pitchers usually lack these. The colour of the pitcher varies from yellow to scarlet. N. × kinabaluensis seems to produce upper pitchers more readily than either of its parents. In all respects N. × kinabaluensis is intermediate between the two parent species and it is easy to distinguish from all other Nepenthes of Borneo. However, it has been confused once before, when the hybrid was labelled as N. rajah in Letts Guide to Carnivorous Plants of the World (Cheers, 1992).[81]

N. × kinabaluensis was first collected near Kambarangoh by Lilian Gibbs in 1910 and later mentioned by Macfarlane as "Nepenthes sp." in 1914.[82] Although Macfarlane did not formally name the plant, he noted that "[a]ll available morphological details suggest that this is a hybrid between N. villosa and N. rajah".[83] It was finally described in 1976 by Kurata as N. × kinabaluensis. The name was published in Nepenthes of Mount Kinabalu, though the specific epithet "kinabaluensis" is a nomen nudum, as it was published with an inadequate description and lacked information on the type specimen. The name was subsequently republished by Kurata in 1984[84] and by Adam and Wilcock in 1996.[85]

Hybrid or species?

It is worth noting that N. × alisaputrana and N. × kinabaluensis are often fertile and thus may breed among themselves. Clive A. Stace writes that we may speak of "stabilised hybrids when they have developed a distributional, morphological or genetic set of characters which is no longer strictly related to that of its parents, ... if the hybrid has become an independent, recognisable, self-producing unit, it is de facto a separate species".[86] N. hurrelliana and N. murudensis are two examples of species that have a putative hybrid origin. N. × alisaputrana and N. × kinabaluensis are sufficiently stabilised that a species status has been discussed.[14] Indeed, N. kinabaluensis was described as a species by Adam & Wilcock in 1996. However, this interpretation does not have much support in the scientific community and the name has not been published in any other work since.

Due to their dioecious nature, a hybrid involving a pair of Nepenthes species can represent one of two possible crosses, depending on which species was the female and which was the male. When the cross is known, the female (or pod) parent is usually referred to first, followed by the male (or pollen) parent. This is an important distinction, as the hybrid will usually display different morphological features according to the type of cross; the pod parent is thought to be dominant in most cases and hybrid offspring usually resemble it more than the pollen parent. Most wild plants of N. × kinabaluensis, for example, show a greater affinity to N. rajah than N. villosa and are thus thought to represent the cross N. rajah × N. villosa. However, specimens have been found that seem to be more similar to N. villosa, suggesting that they might be the reverse cross (see [4]). The same is true for other hybrids involving N. rajah. It is unknown whether these crosses are fertile or not and this element of uncertainty only adds to the confusion over the distinction between a stable hybrid and a species.

Cultivation

- See also: Nepenthes cultivation

Nepenthes rajah has always been considered to be one of the more difficult Nepenthes species to cultivate. However, in recent years, it has become apparent that the plant may not be deserving of its reputation.

Environmental factors

N. rajah is a montane species or "highlander", growing at altitudes ranging from 1500 to 2650 m. As such, it requires warm days, with temperatures ranging (ideally) from approximately 25 to 30 ℃,[87] and cool nights, with temperatures of about 10 to 15 ℃.[87] Here, it is important to note that the temperatures themselves are not vital (when kept within reasonable limits), but rather the temperature drop itself; N. rajah needs considerably cooler nights, with a drop of 10 ℃ or more being preferable. Failure to observe this requirement will almost certainly doom the plant in the long term or, at best, limit it to being a small, unimpressive specimen.

In addition, like all Nepenthes, this plant needs a fairly humid environment to grow well. Values in the region of 75% R.H.[87] are generally considered optimal, with increased humidity at night (~90% R.H.). However, N. rajah does tolerate fluctuations in humidity, especially when young, provided that the air does not become too dry (below 50% R.H.). Humidity can be easily controlled using an ultrasonic humidifier in conjunction with a humidistat.

In its natural habitat, N. rajah grows in open areas, where it is exposed to direct sunlight – it therefore needs to be provided with a significant amount of light in cultivation as well. To meet this need, many growers have used metal halide lamps in the 500–1000 watt range, with considerable success. The plant should be situated a fair distance from the light source, 1 to 2 m is recommended.[87] Depending on location, growers can utilise natural sunlight as a source of illumination. However, this is only recommended for those living in equatorial regions, where light intensity is sufficient to satisfy the needs of the plant. A photoperiod of 12 hours is comparable to that experienced in nature, since Borneo lies on the equator.[87]

Potting and watering

Pure long-fibre Sphagnum moss is an excellent potting medium, though combinations involving any of the following – peat, perlite, vermiculite, sand, lava rock, pumice, Osmunda fibre, orchid bark and horticultural charcoal – may be used with equal success. The potting medium should be well-drained and not too compacted. Moss is useful for moisture retention near the roots. The mix should be thoroughly soaked in water prior to potting the plant.

It has been noted that N. rajah produces a very extensive root system (for a Nepenthes) and, for this reason, it is recommended that a wide pot be used to allow for proper development of the root system.[87] This also eliminates the need for frequent re-potting, which can lead to transplant shock and the eventual death of the plant.[87]

Purified water should be used for watering purposes, although 'hard water' is tolerated. This is done to minimise the build-up of minerals and chemicals in the soil. Water purity greater than 100 p.p.m. of total dissolved solids is often quoted as ideal.[88] A reverse osmosis unit can be used to filter the water or, alternatively, bottled distilled water can be purchased. Watering should be done regularly. However, plants should not be allowed to sit in water, as this may lead to root rot.

.jpg)

Feeding and fertilising

N. rajah is a carnivorous plant and, as such, supplements nutrients gained from the soil with captured prey (espescially insects) to alleviate deficiencies in important elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Just as in nature, a cultivated plant's 'diet' may include insects and other prey items, although this is not necessary for successful cultivation. Crickets are recommended for their size and low cost. These can be purchased online or at specialist pet stores. They can simply be dropped into the pitchers by hand or placed inside using metal tongs or similar, whether dead or alive.

From trials carried out by a commercial Nepenthes nursery,[89] it appears that micronutrient solutions have "a beneficial effect on plants of improved leaf colouration, with no deleterious affects" as far as can be seen. However, more research is required to verify these results. Actual fertilisers (containing NPK) were, on the other hand, found to "cause damage to plants, promote pathogens and have no observable benefits". Hence, the use of chemical fertilisers is usually not advised.

It is important to note that N. rajah is a very slow growing Nepenthes. Under optimal conditions, N. rajah can reach flowering size within 10 years of seed germination, although it is thought that it may take 100 years to reach full size. Theoretically, given climatic conditions do not change, N. rajah has an indefinite lifespan.

Common misconceptions

Nepenthes rajah has been a well known and highly sought after species for over a century and, as a result, there are many stories woven around this plant. One such example is the famous legend that N. rajah grows exclusively in the spray zones of waterfalls, on ultramafic soils. Although the latter is true, N. rajah is certainly not found solely in the spray zones of waterfalls and this statement seems to have little basis in fact.[2] It is likely this misconception was popularised by Shigeo Kurata's 1976 book Nepenthes of Mount Kinabalu, in which he states that "N. rajah is rather fond of wet places like swamps or the surroundings of a waterfall".[7]

This being the case, certain N. rajah plants do in fact grow in the vicinity of waterfalls (as noted by H. Steiner, 2002) "providing quite a humid microclimate",[14] which may indeed be the source of this particular misconception.

Another myth surrounding this species is that it occasionally catches small monkeys and other large animals in its pitchers. Such tales have persisted for a very long time, but can probably be explained as rodents being mistaken for other species.[90] It is interesting to note that one common name for Nepenthes plants is 'Monkey Cups'. The name refers to the fact that monkeys have been observed drinking rainwater from these plants. Thus, in a sense, this mythology may have some basis in fact.

Timeline

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Clarke, Cantley, Nerz, Rischer & Wistuba 2000.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Clarke 1997, p. 123.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hooker 1859.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Clarke 1997, p. 122.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Focus: Rajah Brooke's Pitcher PlantPDF (111 KiB)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Phillipps 1988, p. 55.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Kurata 1976, p. 61.

- ↑ Masters 1881.

- ↑ Reginald 1883.

- ↑ Hemsley 1905.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Danser 1928, 38.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Phillipps & Lamb 1996, p. 129.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gibson 1983.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Steiner 2002, p. 94.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Clarke 1997, pp. 120, 122.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, pp. 10, 120.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Clarke 2001b, p. 7.

- ↑ Clarke 2001b, p. 26.

- ↑ Clarke & Kruger 2005.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Clarke 1997, p. 120.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Clarke 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ Walker, Matt (10 March 2010). "Giant meat-eating plants prefer to eat tree shrew poo". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8552000/8552157.stm. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Chin, L., J.A. Moran & C. Clarke 2010. Trap geometry in three giant montane pitcher plant species from Borneo is a function of tree shrew body size. New Phytologist 186 (2): 461–470. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03166.x

- ↑ Moran 1991.

- ↑ "I once found a perfect mouse skeleton in a pitcher of N. rafflesiana" — Ch'ien Lee

- ↑ [Anonymous] 2006.

- ↑ Beaver 1979, pp. 1–10.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Tsukamoto 1989, p. 216.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Tsukamoto 1989, p. 220.

- ↑ Edwards 1931, pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Burbidge 1880.

- ↑ St. John 1862, pp. 324, 334.

- ↑ Phillipps & Lamb 1996, p. 20.

- ↑ [Anonymous] 1881.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Phillipps & Lamb 1996, p. 22.

- ↑ Phillipps & Lamb 1996, p. 21.

- ↑ Phillipps & Lamb 1996, p. 18.

- ↑ Ellis 2000.

- ↑ Beck von Mannagetta, G. Ritter 1895.

- ↑ Macfarlane 1908, pp. 1–91.

- ↑ Clarke 2001a, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Clarke 2001a, p. 82.

- ↑ Fairbrothers, Mabry, Scogin & Turner 1975.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Adam, Omar & Wilcock 2002, p. 623.

- ↑ Som 1988.

- ↑ Jay & Lebreton 1972, pp. 607–613.

- ↑ Adam, Omar & Wilcock 2002, p. 624.

- ↑ Meimberg et al. 2006

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Meimberg et al. 2001

- ↑ Nerz & Wistuba 2007.

- ↑ Sabah Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment Homepage

- ↑ Adlassnig, Peroutka, Lambers & Lichtscheidl 2005.

- ↑ Clarke 2001b.

- ↑ Kaul 1982.

- ↑ Vegetation Zones on Mount Kinabalu

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p. 2.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p. 29.

- ↑ Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997

- ↑ APPENDICES I AND II as adopted by the Conference of the PartiesPDF (120 KiB)

- ↑ Creek, M. 1990. The conservation of carnivorous plants.PDF Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 19(3–4): 109–112.

- ↑ Clarke 2001b, p. 29.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Simpson 1991.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p. 172.

- ↑ Nineteenth meeting of the Animals Committee. Geneva (Switzerland), 18–21 August 2003.

- ↑ Clarke 2001a, p. 236.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Clarke 2001b, p. 38.

- ↑ Malouf 1995, p. 68.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p. 143.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 A rare find: N. rajah nat. hybrid. Flora Nepenthaceae.

- ↑ Steiner 2002, p. 124.

- ↑ Arx, Schlauer & Groves 2001, p. 44.

- ↑ Adam & Wilcock 1992.

- ↑ Clarke 2001b, p. 10.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p. 157.

- ↑ Slack 1986.

- ↑ Clarke 1997, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Kurata 1976, p. 65.

- ↑ Clarke 2001b, p. 19.

- ↑ Cheers 1992.

- ↑ Kurata 1976, p. 64.

- ↑ Macfarlane 1914, p. 127.

- ↑ Kurata 1984.

- ↑ Adam & Wilcock 1996.

- ↑ Stace 1980.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 87.3 87.4 87.5 87.6 On the Cultivation of Nepenthes rajah

- ↑ D'Amato 1998, p. 7.

- ↑ Nepenthes Cultivation and Growing Guides

- ↑ D'Amato 1998, XV.

References

|

|

Further reading

- Camilleri, T. 1998. Carnivorous Plants. Kangaroo Press, Roseville, New South Wales, Australia. 104 pp.

- Jebb, M. H. P. & M. R. Cheek 1997. A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae). Blumea 42 (1): 1–106.

- Slack, A. 1979. Carnivorous Plants. Alphabooks, Dorset, UK. 240 pp.

External links

General

Images

- Photographs of N. rajah in its natural habitat

- Images of N. rajah in natural habitat and tissue culture

- Borneo Exotics: Nepenthes rajah

Cultivation

- N. rajah Cultivation Notes

- Further Cultivation Notes

- Colorado Carnivorous Plant Society: Nepenthes rajah

- Growth of plant in cultivation over several years

- Large plants in cultivation

Other

- The International Plant Names Index: Nepenthes rajah

- Nepenthes rajah entry from Danser's Monograph

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Nepenthes rajah

- Video about Nepenthes rajah from The Private Life of Plants

|

N. adnata |

N. clipeata |

N. hamata |

N. macfarlanei |

N. palawanensis |

N. spathulata |

Incompletely diagnosed taxa: N. sp. Misool • N. sp. Palawan • N. sp. Papua • N. sp. Sulawesi

Possible extinct species: N. echinatus • N. echinosporus • N. major

|

N. × alisaputrana |

N. × ferrugineomarginata |

N. × kuchingensis |

N. × pyriformis |

N. × truncalata |

General: Over het geslacht Nepenthes (1839) • Über die Gattung Nepenthes (1872) • Nepenthaceae (1873)

Die Gattung Nepenthes (1895) • Nepenthaceae (1908) • The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies (1928) • Nepenthaceae (1936)

A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae) (1997) • Nepenthaceae (2001) • Pitcher Plants of the Old World (2009)

Regional: Nepenthes of Mount Kinabalu (1976) • Nepenthes di Sumatera (1986) • An account of Nepenthes in New Guinea (1991)

Pitcher-Plants of Borneo (1996, 2008) • Nepenthes of Borneo (1997) • Nepenthes of Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia (2001)

Nepenthesin • Nepenthales